Sociotechnical Architecture as Enabler of Product Thinking

TL;DR: This article provides an overview on several ideas I have been exploring on how Sociotechnical Architecture and Systems Thinking are key to enabling achieving the goals of Product thinking: "maximize the value exchange with the customer, continuously and at high-velocity". The core elements of the article were initially presented on my DDD EU 2021 talk [DDD_EU-Silva], but this article explores them further. In this article I do not go into “how to implement these ideas”, “who should do this”, etc. Those elements are explored in other articles and material (some still work-in-progress), which you will be able to find on my Sociotechnical Architecture & Systems page [Sociotech-Arch-Silva].

Product Thinking

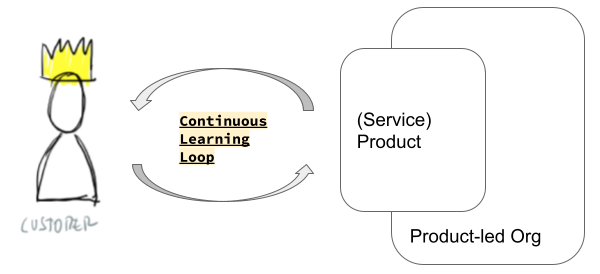

Product thinking [Escaping-Build-Trap-Perri, Product-Thinking-101-Katakam] has been gaining traction as a customer-centric approach to product development, i.e.: customer becomes the main driving force for product development. Apart from customer-centricity, there is also a clear focus on “outcome” rather than sheer “output”. This is my one sentence summary of Product Thinking: it is about customer-centric product discovery, delivery and evolution (while still taking into account the business goals). Figure below depicts its main elements.

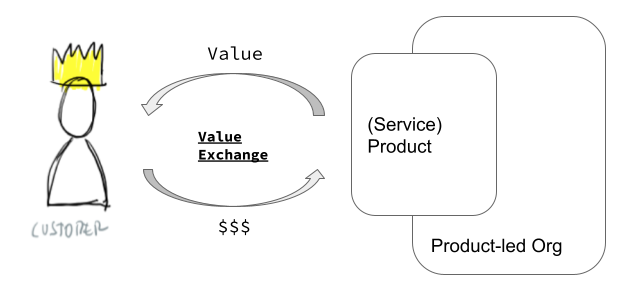

As it can be seen, the goal of Product Thinking is to build and evolve the product based on a “continuous learning loop” with the customer. This is the key differentiation from classical “sales-driven” and “tech-enabled” product development models, which tend to prioritize other elements, not the real problems of the customer, and consequently becoming not be able to maximize the value exchange with the customer. Melissa Perri [Escaping-Build-Trap-Perri] summarizes Product Thinking priorities rather well in the following remark: “our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software”. “Valuable software” can mean different things, but it is key that our efforts as organization are tuned into “maximizing the value exchange with customer”, i.e.: we deliver and evolve the product to satisfy the customer problems (i.e.: build a product driven by the customers’ “problem space”), so that we support solving a customer is challenge/problem, and with that customers are happy and consequently willing to pay for the value the product brings.

With this mental model and goal, the next question we can ask ourselves is: “how can we achieve that”, i.e.: maximize the value exchange with the customer continuously and at high-velocity? There are a lot of factors that contribute to that. One important remark is: we are talking about products, not projects. This is a key distinction, as a project is an iteration on development of something and in general has a clear end goal and scope. On the other hand products tend to continuously evolve and be improved based on the learnings and needs we discover with the customer.

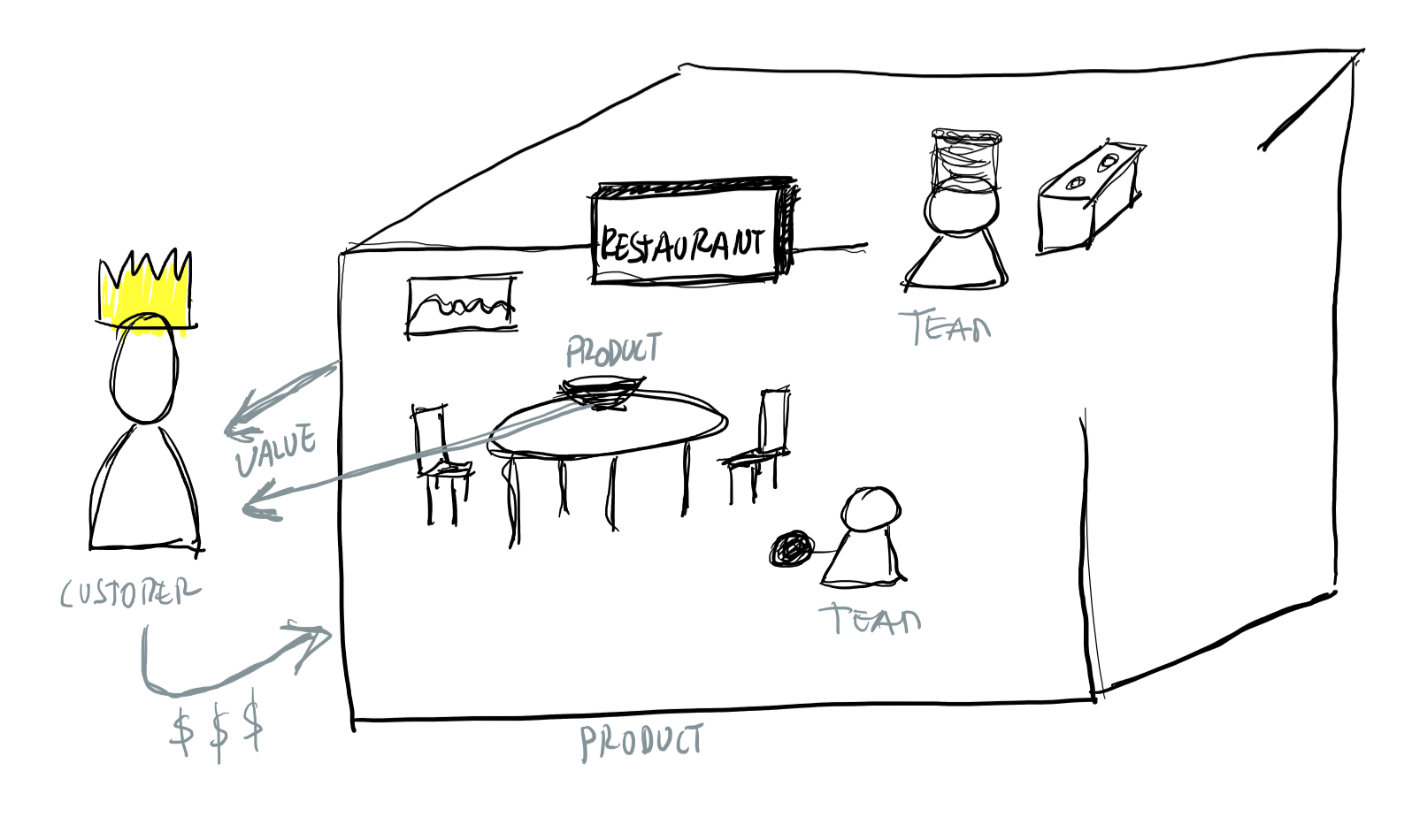

In the following I go over a few system traits that need attention when addressing product development and evolution. I will use my “Restaurant Product” running example to showcase those different traits. You can find a more detailed intro to this example and traits in this article of intro to sociotechnical architecture series.

(Some System) Traits for Great Tech-enabled Products

Trait 1 - your teams and org shape your product

Whatever product we are building, we need to make sure the team (and its setup, organizational architecture and communication structures) is aligned with the ambitions we have for the product being designed (the actual “technical architecture” of the product). This is basically Conway’s Law [Conways-Law], i.e.: “Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

Restaurant example: if we want to build a great French food and drinking experience restaurant, we need to have good French chefs and wine experts who are set up to work together on building a product that brings those elements together as a great experience for the customer.

Trait 2 - your teams must have the right conditions to build the product for your customer

This basically means that your teams should have the right scope and capacity to build the product for the customer. So, when shaping the product to be built, we must explicitly consider the teams (and their topology and setup) in order to actually be able to make it to work. This is where the work of Team Topologies [Team-Topologies] - and their “team-first approach” can help a lot. Neglecting teams on the process of architecting the systems at play - and purely focus on the desired product (and its Technical Architecture) will (almost certainly) lead to surprises on the actual building, delivering and evolving of the product.

Restaurant example: in order to have a restaurant running smoothly and continuously creating the best customer experiences, we need to have enough people cooking, serving and doing all the different activities of the restaurant. We cannot expect Chefs to cook, serve the food and do the dishes at the same time.

Trait 3 - Your product is a combination of value streams owned by different teams but aligned to maximize value exchange with customer

A product can be seen as a system with different parts that together (and with their interactions) define and deliver the value the customer seeks. We want those different value streams to come together in a harmonious way for our customer. We do not want local “siloed” optimizations done without the product (whole system) context and goals in consideration. Such approaches (almost) never lead to the goal we have: maximizing the overall value exchange with the customer. This holistic understanding approach is a core property of Systems Thinking [System-Thinking-Ackoff], which still tends to be very much ignored by many modern approaches to product development - which tend to focus on “reductionism” [Good-Fences-Hjorteland] and breaking the system into independent parts developed in isolation.

Restaurant example: in our restaurant we don’t want to simply serve the “best dish we can cook” combined with the “best wine we have”. That combination of what is the best in each part does not necessarily lead to the best end product for our customers. The best outcome results from a contextual combination of parts, which requires interaction and understanding while designing the experience (i.e.: let’s cook this dish and combine it with that wine because these are great fresh ingredients and that wine is really good and their combination will be an amazing experience).

Trait 4 - Your teams should be empowered to discover (with the customer) what are the best things to build in the product

A cornerstone of Product Thinking is to enable teams to listen, discover and understand the customer’s problems, and be empowered to map that into product developments that can address those problems. In order to achieve this teams need to be on the driving seat of “discovery & learning” activities with the customer. Failing to do that - and having teams owning and evolving the product far from the customers, behind several “layers of other teams/people”, will lead to poorer understanding of the customer. Furthermore, it will also lead to a much slower product development life cycle (and lead time to implement developments - which is a well known metric to measure high-performance, as described on Accelerate book metrics [Accelerate]). Even when teams do discovery, it is also important to make sure that the whole team is enabled to do product discovery. This is not a job for just a few people in the team (e.g.: UX). Teams are one of the main drivers of great product development ideas [PM-Research-Alpha] , so making sure this can happen is crucial.

Restaurant example: we want the people working on the kitchen to understand how customers are reacting to their dishes, so they can tweak and evolve them. For example, they may need to understand if the produce they use is working fine. If not, they may need to look for alternative sources. Cooks and kitchen staff will be the most equipped to reason on these discovery activities. Note: again, those discovery activities are done with a wider understanding, e.g.: how are we combining the dish with wines or how are we plating and serving the dish to customers.

Not just “What”, but also “Who” + “How” Systems… Holistic Understanding!

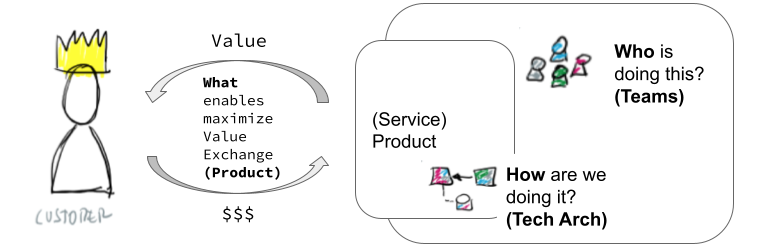

If we analyse the traits presented in the previous section, we can see that in order to achieve the goal of Product Thinking we cannot purely focus on “What enables maximum value exchange” (the “What” system). We must also cater for other important interrelated systems, namely: “Who” is listening to the customer and building/evolving the product; and “How” is the product being built to deliver the value maximization the “What” discovers and defines. Furthermore, how do all these parts interrelate and gather relevant understanding to drive meaningful decisions that positively affect the whole system. Figure below depicts a visualization of these three parts.

These (What, Who and How) are all relevant systems on the overall goal equation of Product Thinking. It is fundamental to embrace that they must be understood from an holistic perspective in order to define strategies to improve our overall system goal. For example: to improve our Restaurant, we consider the offerings we have (“What” system), but also the crew we have and how they are organized (“Who” system) and how they build the dishes and different experiences for the customers (“How” system). They are all interrelated and their relations define the Restaurant (System).

These ideas build upon the Systems Thinking ideas [System-Thinking-Ackoff], which defines that in order to truly understand to improve a system (e.g.: make it more effective), it must be contextualized and understood from the perspective of the “bigger system” it is part of. We don’t want each part of the “bigger system” to be evolved in isolation, that would mean local optimizations with no context of the whole system, which normally defines value to customer. For example, we don’t want to be “just cooking the best dishes we can think of”, without any sense of what is happening in the rest of the Restaurant and the experiences we want to optimize for our customers. Such local optimizations tend to lead to suboptimal results, and in many cases different systems may “arm” each others’ improvements. Russel Ackoff has a great quote on this, namely: “…understanding proceeds from the whole to its parts, not from the parts to the whole as knowledge does”.

Now the challenge is: how can we apply these ideas to build Tech-enabled products? In the next section I share some ideas on this.

Sociotechnical Architecture - holistic evolution of What, Who and How systems

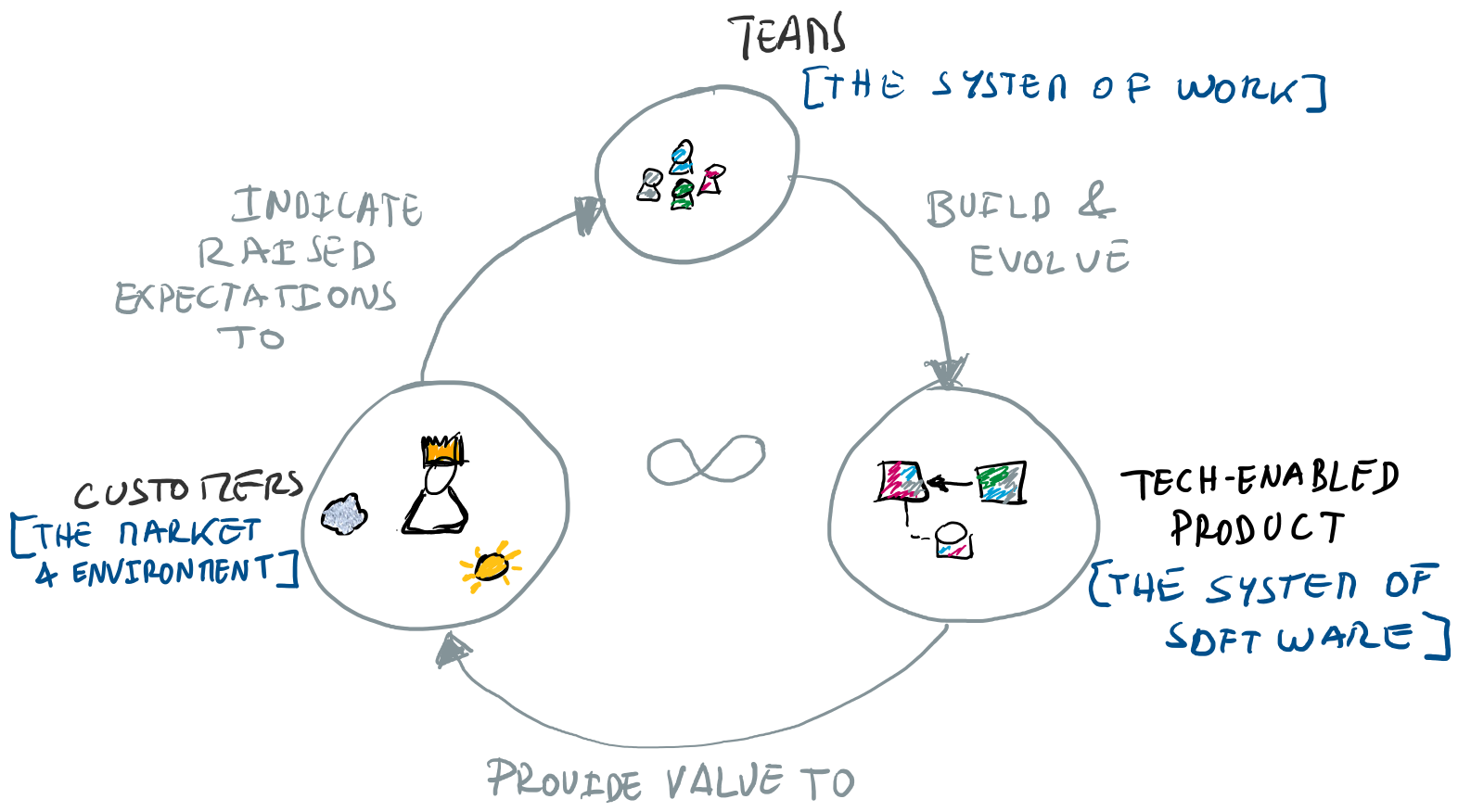

Building on the Systems Thinking perspective, the figure below depicts the mental model I am using to define the “involving system” (or “bigger system”) to define an holistic approach to understand and evolve the systems at play when building tech-enabled products.

This is a sociotechnical system model, with three main parts/systems: the Customers (or market); the Teams (or systems of work, or organizational system); and the Software Architecture (system of software or technical systems). It also depicts their interactions, defining in this way how they normally affect each other. The goal is to have a clear model that provides a framework for a more holistic understanding and from there approach the design and evolution of the different parts with context. This activity is what I call “Sociotechnical Architecture” [Sociotech-Arch-Silva]:

…taking an holistic co-design approach to technical and organizational systems, given the inherent impact they have on each other.

Important to note that technical and organizational systems tend to be driven by context of the market and customers the product is targeting.

There are many further considerations to take on this, which I elaborate in other articles [Sociotech-Arch-Silva]. However, the bottom-line is: for relevant (architectural) decisions it is important to start from the holistic understanding, i.e.: what are the important elements that each system parts and their interactions have at the moment that should be “understood” to enable the evolution of our overall systems and its parts? This provides a solid evolution framework for approaching Product Thinking implementation and scaling in organizations.

It is key to understand that the system parts depicted encapsulate other sub-systems and a similar approach for understanding and evolution can be applied to those systems (e.g.: product teams working on a specific value stream consolidate understanding from the holistic value stream perspective, not per team, which then provides clearer context for each team contributing to a particular value stream). Last but not the least: all of these (encapsulated systems) are interrelated.

Important: this framework of thinking and architecting does not mean we must have a full-upfront design of all the different parts (and all their internal details) together, and in a sense “compromise” the autonomy of execution of the different parts. It simply means that it is important to have feedback loops of elements that are relevant for the holistic understanding, so that we can have a clearer understanding on the necessary decisions from the holistic system perspective. That understanding and context provide well grounded data to drive decisions on the system parts (product, organization and technical architecture design and evolution). Ruth Malan and Dana Bredemeyer have a great article [Minimalistic-Architecture-Malan-Bredemeyer] discussing this balancing act of “how much architecture decisions” shall we “drive” from the involving system and not. They propose an approach of “minimal architecture” and I couldn’t agree more. The goal, as they state is to focus on the “essential decisions, ones the identify the system’s key structural elements, the externally visible properties tof those elements and their relations”. In the case of Sociotechnical Architecture, this means we must have sensors on the “structural elements, visible properties and relations” of the What, Who and How systems, and based on those signals derive context (understanding) that can drive the evolution of the sociotechnical system.

What’s next?

First things first, it is primordial to stop silo-based thinking, every system and work is always part of a “bigger system” and that is where you need to drive alignment and understanding for building and evolving your system (being it in this case, our teams or the technical architecture). This is not trivial and may mean very different things per organization. Nevertheless, there are some basic elements that we can start working on, e.g.: enable teams to be properly set up and aligned with the product we want to build.

However, whatever step you need to take keep in mind, it is just the first step. The ideas shared here build on the premise that systems are in “continuous evolution”, i.e.: don’t see the step you take as yet another transformation project with a specific end result. Approach Sociotechnical Architecture as an iterative evolution approach to keep your sociotechnical systems effective on building the product and delivering value to customers at high-velocity.

I am writing more on this, namely: how to approach Sociotechnical Architecture evolution and who may be needed to make sure that this system evolution is catered for (these articles will be published on my Sociotechnical Architecture and Systems page - follow me on twitter to be notified of updates).

Appendix: DDD EU conference talk video & slides

References

- [DDD_EU-Silva] Sociotechnical Architecture as Enabler of Product Thinking, Talk on Domain-Driven Design Europe 2021, Eduardo da Silva

- [Sociotech-Arch-Silva] Sociotechnical Architecture, Eduardo da Silva

- [Escaping-Build-Trap-Perri] Escaping the Build Trap, Melissa Perri

- [Product-Thinking-101-Katakam] https://uxplanet.org/product-thinking-101-1d71a0784f60, 2020, Naren Katakam

- [Conways-Law] Conway’s Law, Melvin Conway

- [Team-Topologies] https://teamtopologies.com, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais

- [System-Thinking-Ackoff] TLA_insights: On Systems Thinking, Russel Ackoff, Russel Ackoff

- [Good-Fences-Hjorteland] TLA_insights: Good Fences, Trond Hjorteland, Trond Hjorteland

- [Accelerate] Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations, Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, Gene Kim

- [PM-Research-Alpha] How Product Management is Evolving: Findings from the 2020 PM Insights Report, Alpha

- [Minimalistic-Architecture-Malan-Bredemeyer] Less is More with Minimalist Architecture, Ruth Malan and Dana Bredemeyer, 2002

Conversation

📣 New article "Sociotechnical Architecture as enabler of Product Thinking": to "maximize the value exchange with customer" we must enable and evolve the supporting Sociotechnical system with holistic understanding.

— Eduardo da Silva (@emgsilva) May 3, 2021

check it here ⤵️https://t.co/yLwRj5LSni

ℹ️ I offer consulting services and products on this topic

If you are looking for help on these topics feel free to contacting me, and/or check my consulting and products pages for more details on how I may be of help.