Introduction to Sociotechnical Architecture: Traits and Strategies

TL;DR: this is the second article of my "Introduction to Societechnical Architecture" series. In this series I cover why Sociotechnical Architecture is so relevant, what is it and how to start "doing it" when setting up your organization and strategies to build software products. In this article I will revisit all the different traits introduced in the first article (to set up a "Successful Restaurant") and elaborate on them in the context of building software products and the teams that own them. I will go over what is behind each trait, then share some strategies to address them. (Work-in-progress: I will be adding real-life examples on each of the traits, so we can further understand and consolidate each trait).

If you did not read the first article of the series (where I provide a motivation - “Why” - and an overview of what is Sociotechnical Architecture) you can check it here. Overview of the whole series can be found here.

Index:

- Introduction

- Trait 1: Conway’s Law

- Trait 2: Team Cognitive Load

- Trait 3: Team Boundaries & Interrelations

- Trait 4: Continuous Discovery & Delivery in Team

- Trait 5: Understand your context & Design based on that

- References

- Changelog

Introduction

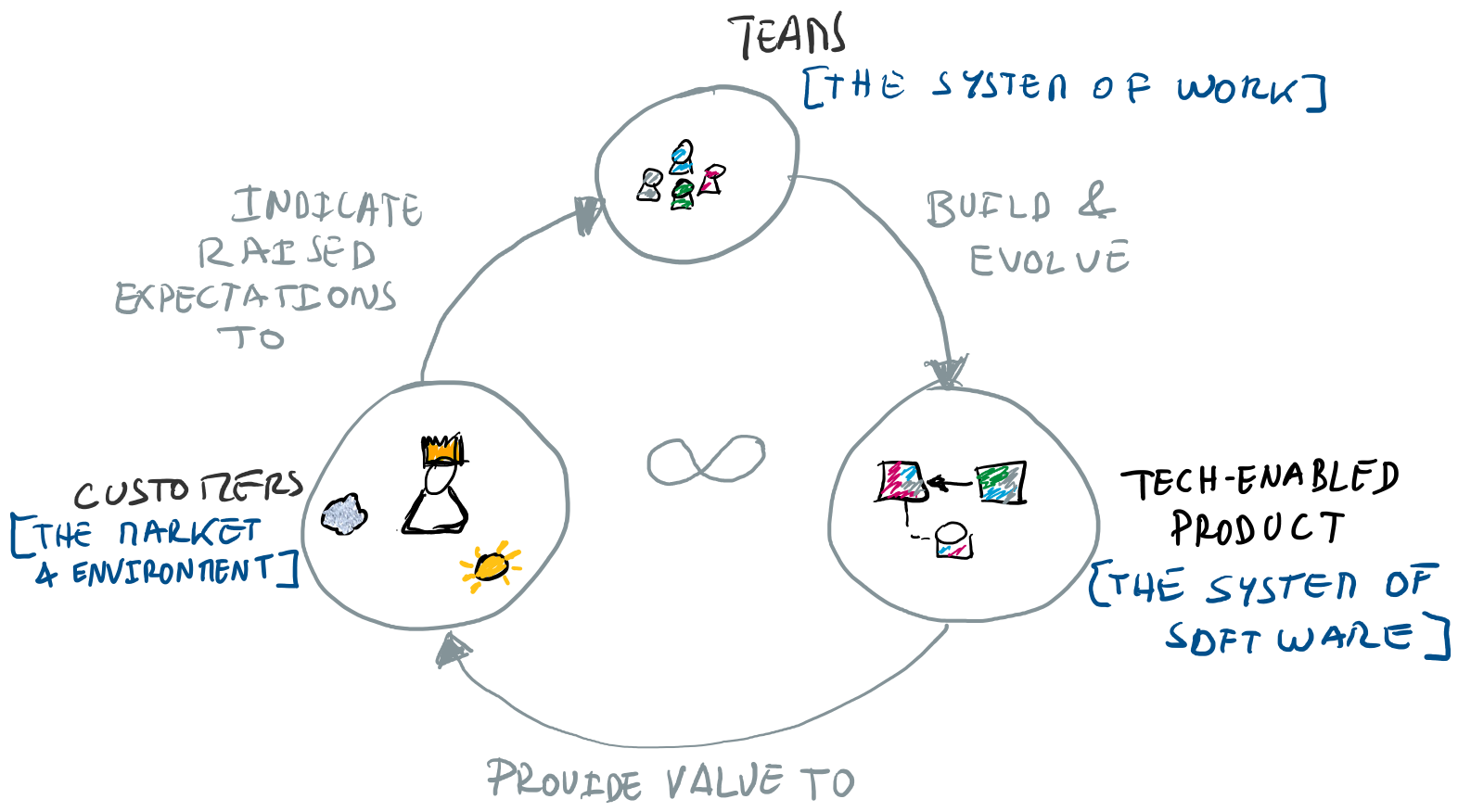

The following diagram sketches a simplified view of the different systems at play when building software products, which basically defines the important dimensions of sociotechnical architecture. I explain these in more depth on the first article of the series.

In this article I will revisit several of the traits of sociotechnical architecture, namely the traits shared in the first article when describing how to set up a “successful restaurant”. However, here we will be positioning them in the world of “building software products”. For each trait I will share the essence and challenge behind the trait, then focus on current strategies and best practices to address them. I finish each trait with an overview of real-world examples to showcase situations where they occur.

Important: there may be other elements and traits that influence the sociotechnical architecture. Nevertheless, the ones presented on this article should provide a good starting point to address sociotechnical architecture.

Trait 1: Conway’s Law ⇦

(Trait 1 in cooking: your staff defines your cooking and experiences)

This trait basically refers to Conway’s law [Conways-Law]:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

In a nutshell: the architecture of your technical system will (eventually) be a mirror of your organizational architecture behind it. This may not be immediate, but as Ruth Malan said [Org-Architecture-Malan]: “If the architecture of the system and the architecture of the organization are at odds, the architecture of the organization wins”. Not knowing this, or not embracing it, can lead to undesirable situations, like, for example: ending up in a situation where HR (who in many organizations is the driving force establishing the org design) end up as “accidental architects” of our Software Systems [HR-Architects].

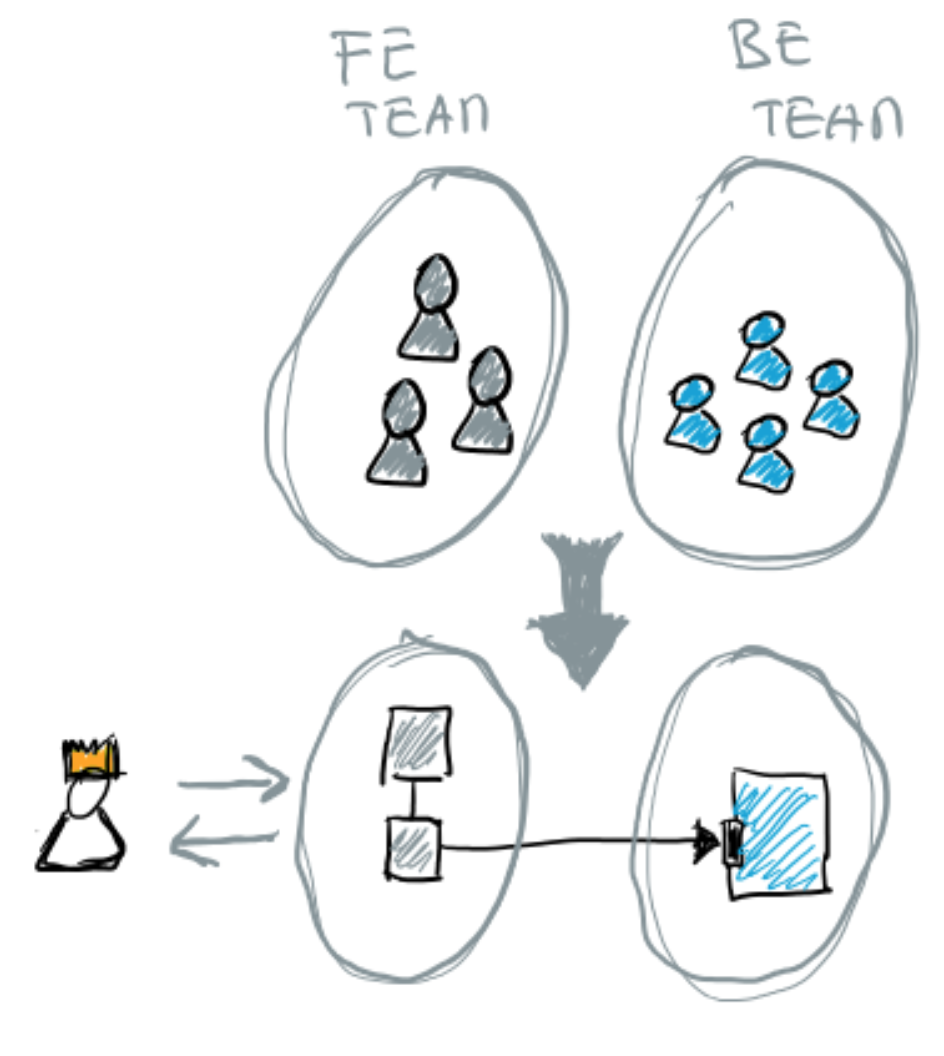

To make this more concrete, let’s assume that we follow the prevalent model of the last decades of setting up teams around disciplines or functions, e.g.: Front-end and Backend teams (and others, such as DB or Data Science, etc.). These teams tend to evolve their technical systems architecture into something similar to the following figure (which basically is a way to enable each function to be able to do their work the best way they can given the organization constraints).

However, this brings a lot of overhead, namely: if we want to develop a new feature in the product (something that the customer sees as a single product, or feature), we will need to define work with all these different teams, align their priorities and “roadmaps” so that they implement the different elements required to build that new feature. This may be needed in some situations (i.e.: have explicit trade-offs that justify having Front-end teams and Back-end teams). However, if not strictly needed and justified it will most likely add a lot of complexity and overhead on the product development activities. This comes from the fact that the same elements (features, or value streams) of the product are owned by multiple teams, as such they need to continuously align on what they need to do, which will decrease their product development velocity (and overall productivity as teams).

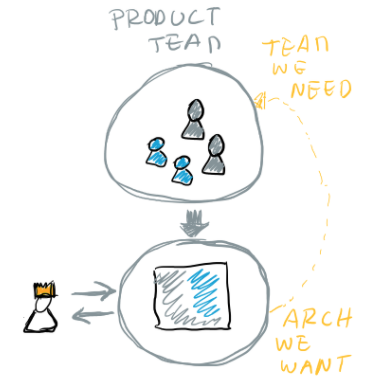

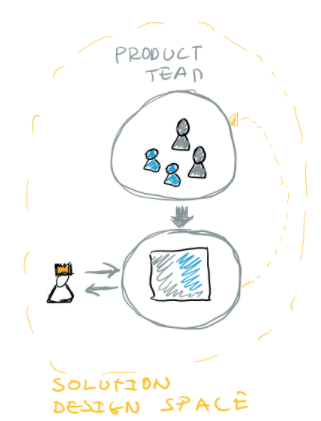

Strategies to address this: Inverse Conway’s Maneuver

To address this unavoidable fact (that is Conway’s law), we can apply the following strategy: first we design the desired technical architecture that will allow us to accomplish our end goal (which can be many different things - but the goal must exist, as it drives the design), and then we see what would be the ideal team setup to own that architecture (in some cases this is an assessment if the existing team(s) is capable of building and owning that new development). This approach has been coined as Inverse Conway’s Maneuver by James Lewis [Inverse-Conways-Maneuver] and it basically boils down into having an explicit co-design of technical and organization architecture. By explicitly considering the org/team design in the solution design space (together with “desired technical architecture”). By considering these two we can really look into what would be the best team(s) formation to achieve our goal and be able to own this new product or development.

Real-World Examples (Work-in-Progress, more stories to follow)

Data Science: from Projects, to Complicated Sub-system Teams to a Discipline in Product Teams (click to expand)

> Work-in-progress

Trait 2: Team Cognitive Load ⇦

(Trait 2: Chefs cannot cook, serve and do the dishes at the same time)

In order to be efficient and quickly build the best for their customer, product teams must properly set up. There are many things that affect teams, one of the major issues comes when teams are asked to do too many things, or their product becomes too complex for them to adequately own. When this happens teams tend to struggle to do what is needed for their product efficiently and furthermore their velocity is affected. For teams to work efficiently they must be able to “fit their product and challenges in their heads” (inspired by Daniel Terhorst-North definition of microservices: “Software that fits in your head” [Microservices-North]).

But how can we understand and validate if this “product fits their heads”? The book Team Topologies [Team-Topologies] provides excellent guidelines to assess that, namely assess the team’s “cognitive load”. Cognitive load basically defines what are the elements that occupy the team’s cognitive power (and capability of doing their work). If we are able to assess this for our teams, we can understand if teams are capable of properly owning their products and if that is not the case, mitigate and take action to address that, so we make sure teams are set to for success.

Understanding what Cognitive Load is and what we can do with it?

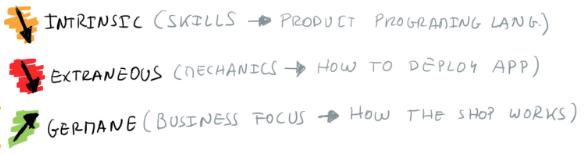

There are three fundamental types of Cognitive Load (for more details check Team Topologies [Team-Topologies]), namely:

- Intrinsic: the skills you need to build your product (e.g.: be able to program in the programming languages and tech stack used to build the software product)

- Extraneous: the activities outside the product development that are required to make the product life (e.g.: be able to understand the infrastructure and processes required to deploy the application)

- Germane: the elements related with the business problem the product solves (e.g.: be able to understand how the customers buy on our webshop)

To set up teams for success we want to make sure they spend most of their cognitive load on Germane tasks - i.e.: solving the business problems of the product (what the customer is looking for, what maximizes the value exchange in the product, etc.). We know teams will always have some intrinsic and extraneous load, however when designing our technical architecture and organization we can (must!) cater for systems that enable minimizing load on those dimensions (e.g.: simple tech stacks - to minimize intrinsic; simplified deployment processes and supporting platforms - to minimize extraneous; etc.).

This is a tricky subject as in many cases engineers want to have “full control of all the technical architecture and deployment setup” - spending in this way a lot of cognitive load on intrinsic activities. However, we need to remember that as the tech community our goal is not to spend most of our time tuning Kubernetes, or migrating existing working code to the latest JavaScript framework, but making sure we efficiently build our product in order to maximize the value exchange with the customer. Another dimension that affects this is the fact that many organizations don’t realize the strategic value of having a good platform for all of their product teams to make minimize the cognitive load they spend in extraneous activities (such as setting up and maintaining complex deployment pipelines - that can in many cases be automated into a simple to use platform).

Strategies to address this: Team Topologies’ Team First Approach

To make sure we set up our teams adequately, Team Topologies proposes the “Team First approach”. Basically it means:

- Don’t just ask a team to go implementing the “desired technical architecture”.

- Instead, start by assessing if the team that is supposed to own/build the desired architecture has “enough cognitive load available”.

- guidelines for assessment of team cognitive load can be found in [Cognitive-Load-Assessment]

- If the answer is “the team does not have enough cognitive load”: something must happen, otherwise the team will not be able to adequately own this product.

- What can we do? This really depends on the situation, but the possibilities can go from creating a new team; taking away elements that are overloading the teams cognitive load (e.g.: extraneous cognitive load tasks - such as simplify their operation efforts, etc.); or simply go and iterate on the technical software architecture design to simplify it.

This design approach, where the team is an integral part of the solution design space allows to minimize the chances of “overloading” the team with a technical architecture that they will not be able to properly own. This triggers and supports the discussions that need to happen.

Important note: cognitive load discussion happens at Team-level, not individuals within the team. This is essential and it is important to step away from designing around individuals within the team. We want to have a team setup for success that does not depend/rely on a single person within the team, since that leads to a lot of issues (check [Team-Topologies] for examples on this).

Real-World Examples (Work-in-Progress, more stories to follow)

Teams Extraneous Cognitive Load as a driver for Platform Teams developments (click to expand)

> Work-in-progress

Tech Leads / Software Architects as enabler teams to scale & support Product Teams more efficiently on a large tech-enabled organization (click to expand)

> Work-in-progress

Trait 3: Team Boundaries & Interrelations ⇦

(Trait 3: Restaurant value/experience is the sum of several streams of activities…)

Like a Restaurant creating the right combination of elements (dish, drinks, service, ambiance, etc.) to maximize the “experience and value exchange” with their customers, this should also be the main driver behind our strategies while building software products (and the organization/teams that actually do it). In order to achieve that, we will be combining different product elements (“value streams”), which are (in most cases) developed and owned by different teams within the organization. This is a natural consequence of Trait 2, namely: teams have a finite “cognitive load” available, and as such we will have different parts of the product owned by different teams. Furthermore, products have natural parts, that can be developed independently of each other. This is particularly important on big and/or complex products.

With this premise, we know that in order to set up teams adequately and empowered to move at “high-velocity” (= clear direction + high speed), we must make sure the parts of the product teams will own are well scoped and the teams have enough cognitive load available to own them. To successfully do that, we will need to have an explicit design where we define scopes with clear boundaries within our product, which teams are capable of properly own.

So, this exercise entails:

- 1: understanding which “scopes” (or “boundaries”) we have;

- 2: how can a team (or group of teams) properly own the identifies scopes;

- 3: how to make sure those teams are set to have maximal cognitive load available to continuously build and improve their part of the product.

This boils down to team boundaries and interrelations.

Strategies to address this: Domain-Driven Design (DDD) & Team Topologies

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) [Domain-Driven-Design] and Team Topologies [Team-Topologies] are two excellent resources to strategically identify and define team boundaries and interrelations.

DDD (especially Strategic DDD elements) provides very powerful mechanisms to understand a “domain” and its different parts, i.e.: identify the boundaries within the domain (I will be providing more in-depth details on this in a later article). This process is done from a domain (business and customer) perspective, instead of a technical-driven perspective. This enables having a sustained and reality-grounded discovery and alignment of the parts of the domain, its boundaries and interrelations. Additionally the DDD community has developed many systematic and structured approaches to conduct this domain discovery and scoping (e.g.: Event Storming sessions to discover and align on what are the different parts of the domain, a.k.a.: “bounded contexts”). This discovery and scoping is done by focusing on the language and its meaning in the domain and its different parts, e.g.: “user” in billing has a certain meaning, while in “marketing” there is a different one, i.e.: they most likely are two different bounded contexts. Furthermore, DDD also provides mechanisms to describe how different parts (Bounded Contexts) relate with each other, namely using Context Maps. Context Maps allow us to see the relations and also describe the level (type) of relations that exist - which in a nutshell allow us to reason on the type of team collaboration we will need to create or facilitate. So, DDD provides excellent elements to discover, scope and describe the product and its parts, their boundaries and interrelations.

DDD does not (directly) address the team and org design. This is where combining DDD with Team Topologies has a huge potential. Team Topologies [Team-Topologies] provides a basic lexicon and strategies to define how teams can be set up (types of teams) and the types of interactions they will have. Furthermore, it also provides excellent insights on how can these teams and interactions evolve in time as teams and the organizations dynamics evolve. In a nutshell, the Team Topologies elements are:

-

4 fundamental Team Topologies to design an organization:

- Stream Aligned Teams (SATs): the teams building a part of the product that supports a certain value stream to the customer. These are the teams that build the product value for customers.

- Enabling Teams: facilitate SATs on overcoming obstacles and in that way enable them to do better. Example, Architecture teams may (should) be an enabling team, facilitating SATs on having a clearer “direction” for their developments, especially if product consists of many SATs (architecture helps addressing cross-cutting aspects that in general are not in general owned by any specific SAT).

- Complicated Subsystem Teams: are teams that own complex parts of the landscape, which by being abstracted into such sub-systems that serve SATs enable their applications to be simpler and as such reduce their cognitive load (and in general increate their velocity).

- Platform Teams: focus on building “internal products” that accelerate and simplify how SATs build their own applications (and products). This is done by taking away complexity of SATs, which enables them to have more cognitive load available to work on the business problems.

-

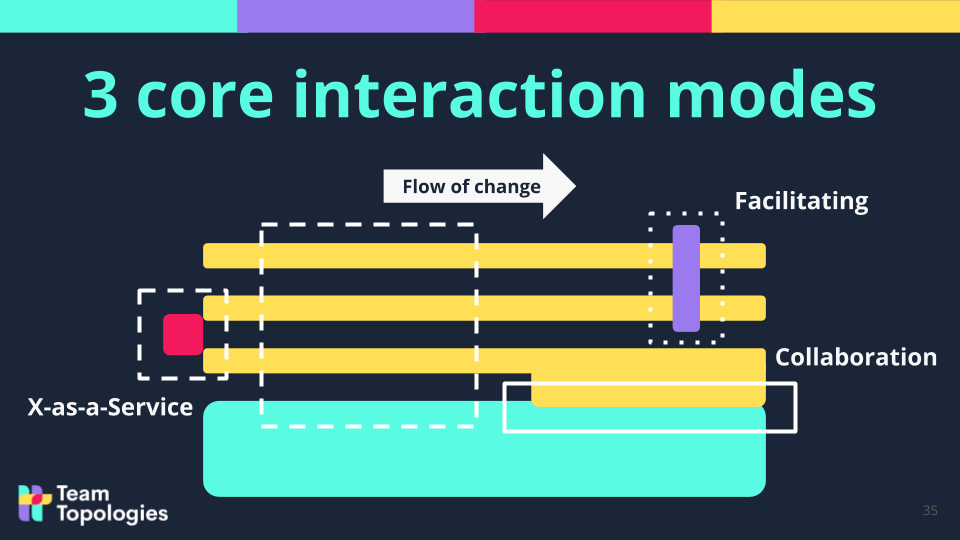

3 core interaction mode for teams:

- Collaboration: interaction mode where two (or more) teams collaborate with each other for a defined period of time to learn and discover how to proceed on their developments (e.g.: identify boundaries of a legacy system and with that each team can own a clear boundary).

- Facilitating: one team helps and mentors another team.

- X-as-a-Service: one team provides another with something “as a service” (e.g.: an API with a clear contract that the other team can consume without the need of continuous collaboration).

(Image Credits: Team Topologies, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais. More insights on the key concepts of Team Topologies here [Team-Topologies-Key-Concepts])

With these core elements we can pretty much design and setup any type of organization. The main goal is to have efficient “Stream-Aligned Teams” (SATs), who can effectively and quickly deliver value to customers. This is achieved by maximizing the cognitive load available on Stream-Aligned Teams. All the other types of teams should have a mission of making sure Stream-Aligned Teams can spend most of their cognitive load to resolve business problems (i.e.: create value).

The interaction modes are very powerful mechanisms to consider while designing teams and their interrelations. For example, we have SATs that may temporarily “collaborate” with each other to discover (sharpen) their scope boundaries. This is normally done by having the members of the two teams working together. Connecting to Trait 2 (Team Cognitive Load), this way of working (where, for example, more than 10 people collaborate together) is not something we want to have for long periods of time. However, it is certainly very beneficial to “discover boundaries” and how scope how to best proceed (basically experiment and learn). Once we learn how to best proceed, we can establish more streamlined interaction modes, e.g.: one team builds a service that the other team uses. This is a powerful element of team topologies: setting clear that organizations are not static and need to evolve, which tends to be in the form of interactions (and the types of teams we need at each moment).

Given this, I see DDD + Team Topologies as an excellent combo strategy to:

- 1: properly scope boundaries and teams relations;

- 2: implement actual org design with teams setup for success (given that they are empowered to properly own their parts of the product - value streams) and how it evolves in time.

(In a later article I will share more insights as of “how to do this” - spoiler alert: the DDD-crew is building excellent elements to help with that)

Real-World Examples (Work-in-Progress, more stories to follow)

Scaling ownership of customer experience and interfaces on large complex products (click to expand)

> Work-in-progress

From Monolith, to Microservices (jungle), to products with clear boundaries and purpose (click to expand)

> Work-in-progress

Collaboration to discover and quickly learn/align teams on how to best move forward autonomously (click to expand)

> Work-in-progress

Trait 4: Continuous Discovery & Delivery in Team ⇦

(Trait 4: don’t hand recipes to your chefs, empower them to discover new recipes!)

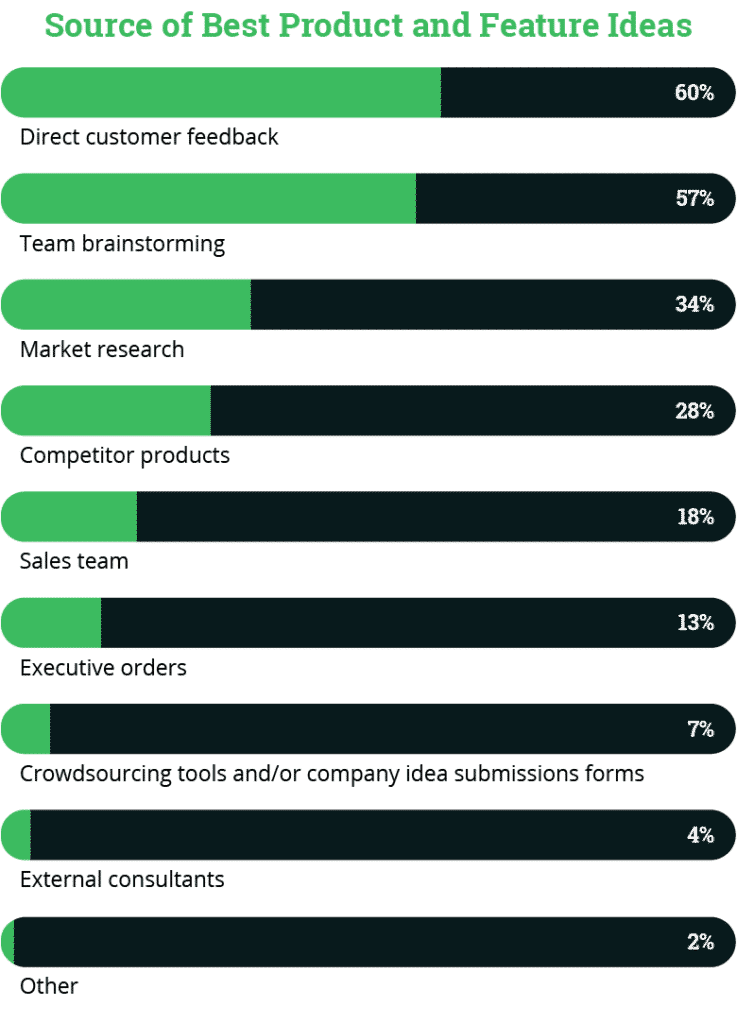

By having an holistic approach to design the software and people systems (“sociotechnical architecture”) we can cater for different elements that enable the conditions for our teams to achieve higher velocity to “build the right things” in their products. One element that is many times overlooked in this is how much the team owning the product (or a value stream within a product) is empowered to actually drive the decisions on “where the product should go”. Classically these decisions are made “top-down” (from outside the team), a bit like pushing recipes to your restaurant chefs, so they can cook them. However, research shows [PM-Research-Alpha] that the best ideas for product development are actually coming from within the team, see Figure below for an overview. These values should not be a surprise as the team is working and developing the product daily, so they develop a deep knowledge of it and the customer, which makes them a natural great source of ideas for improving the product.

(Image Credits: Alpha)

Given this, even if we fully address the elements discussed in Trait 3 and set up teams with clear boundaries and interrelations, we need to also consider that to optimal ownership the team needs to be enabled to drive the developments in the product (as a function of the customer needs). This is a rather important Sociotechnical element to get clear: enable teams to do discovery & delivery of their products continuously.

Strategies to address this: Continuous Discovery & Delivery in the Team

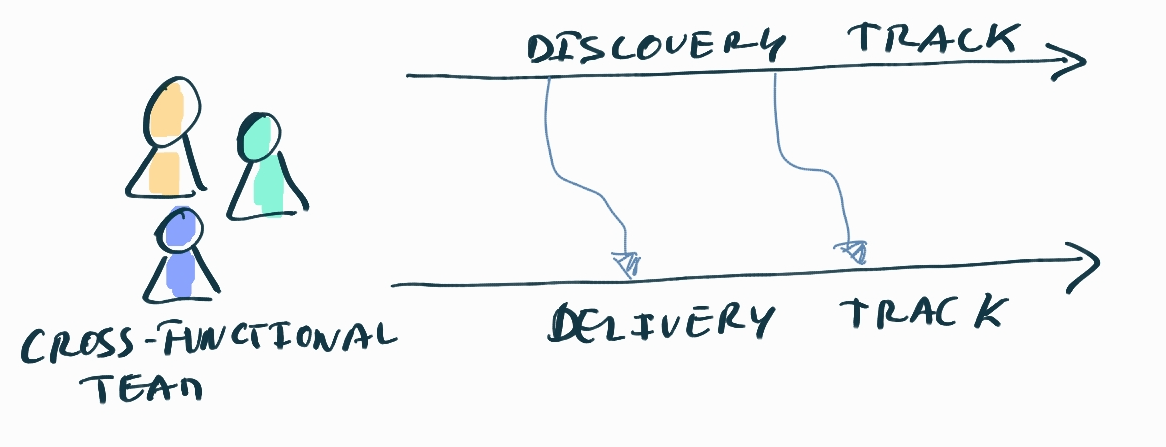

To accomplish Continuous Discover & Deliver in a team we need to enable the team to have time/space to do more “emergent product discovery”. This entails enabling the team to experiment, validate and learn whether the ideas/experiments they have should be promoted to be delivered in the product. What does that mean? The right conditions and ways of working must be in place so that the team can perform “product discovery” activities. One of the major points is to have enough cognitive load (as in Team Topologies [Team-Topologies]) available in the team. To accomplish that the team cannot spend all their cognitive load with “product delivery” activities. This must be considered when assessing the available cognitive load in the team and made explicit as a core principle for the team to operate. If this is not made explicit, delivery activities will (almost always) win, resulting into poor investment on understanding what can maximize the value exchange with customer.

One way to make this explicit is to follow an approach such as “Dual-Track Agile” [Dual-Track-Agile], which makes explicit that teams capacity (cognitive load) is invested on discovery and delivery activities (or tracks). One important remark (which these approaches don’t always make clear) is that “discovery” is not an activity for a certain discipline within the team (in many cases UX people). It is a team activity, and whoever needs to be involved to create the experiment and do the discovery exercise should be involved.

Notes: empowering team to do bottom-up / emergent product discovery does not mean “no top-down” design. These two must coexist in order to identify the best strategies for product development. For example, top-down brings the alignment between multiple products (or value streams), so that we can maximize the overall value exchange with the customer. This is where having Product Management skill within the team helps a lot in managing these different elements.

Real-World Examples (Work-in-Progress, more stories to follow)

... (to expand)

> Work-in-progress

Trait 5: Understand your context & Design based on that ⇦

(Trait 5: because #1 restaurant does something it does not mean it will work for you and your crew)

Every organization has a very particular context, culture and constraints (among many other things, like maturity of their engineering practices, legacy systems, etc.). Blindly copying “operating models” from successful organizations is not a recipe for success. In fact it may lead to many unforeseen issues, given that the model being copied is very specific for the organization that created it.

The most popular example of this is the widespread copying of the “Spotify Model” [Spotify-Engineering-Culture], which has been going on since (aprox.) 2015. Many companies struggling to scale their way of operating and building products found great inspiration on the Spotify Model and adopted many parts of it. Getting inspired is certainly good, but blindly copying is dangerous. As Henrik Kniberg wrote on the original “Spotify Model” article [Spotify-Engineering-Culture]: “This is a journey in progress, not a journey completed, and there’s a lot of variation from squad to squad.”. Nevertheless, many people started copying that “snapshot” of an ever evolving model, i.e.: when they copied it, Spotify most likely had already changed many things on it (as continuous improvement is built-in in the model).

Strategies to address this: Understand your context & design based on that

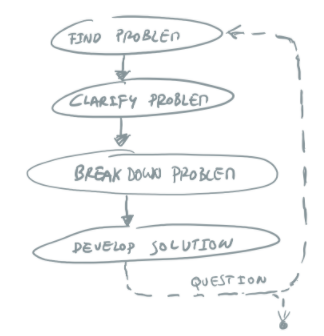

When setting up our sociotechnical architecture and systems we need to understand that this design is so complex and particular to our context, plus it is continuously evolving. Given this, if we want to design our sociotechnical architecture properly we must look at our own organization and technical architectures, and stop the analogy-based thinking (i.e.: copying models that implemented in other organizations).

This means applying more “first principles thinking” [First-Principles], where we understand the problem, break it down into its atomic elements and design solutions from there. We may need to iterate over these steps multiple times.

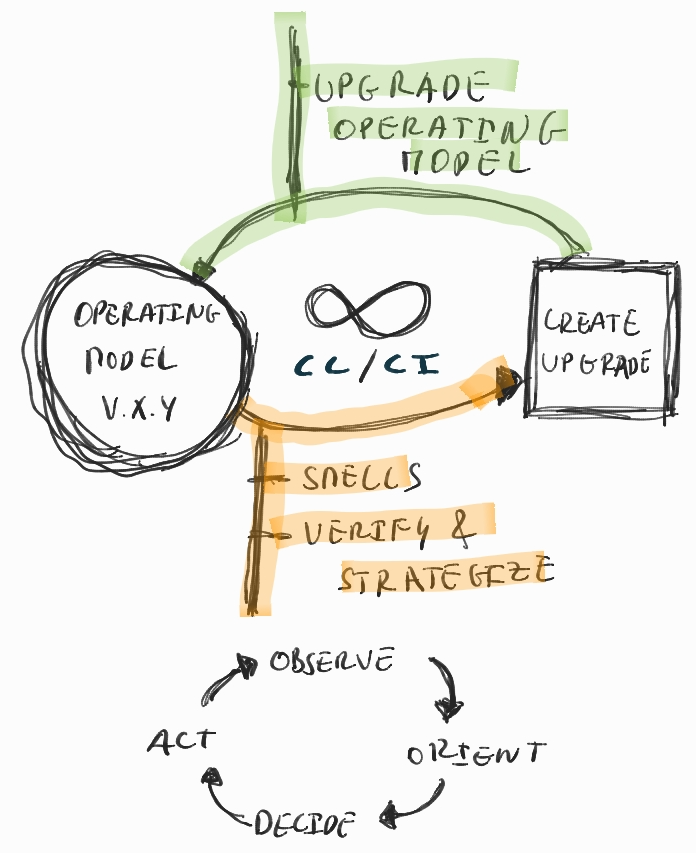

Organizations and their architectures are so dynamic (customer and market changes, internal strategies evolve, people and organization culture mature, etc.) that the “operating model” of our organization’s sociotechnical systems needs to also be continuously updated. So a company’s operating models should not be a fixed model, but an evolving model, see figure below.

Embracing “change” helps us to cater for continuous improvements. I call this “Continuous Change / Continuous Improvement” (CC/CI) model and it is based on the idea of “Target Operating Model” [Target-Operating-Model], where it is envisioned that the organization operating model is continuously changing by creating “upgrades” function of “smells”/issues observed in the organization. This is a rather interesting approach and it has a lot of similarities how we evolved our software development practices: doing more iteratively development and release and stop doing multi-year big iterations. Such big changes are just too difficult, complex and costly (not to mention that we continue operating on a poor model for long time, which produces all sorts of waste).

Real-World Examples (Work-in-Progress, more stories to follow)

Copying Spotify 2015 Snapshot (to expand)

> Work-in-progress

References

- [Conways-Law] http://www.melconway.com/Home/Conways_Law.html, Melvin Conway

- [Org-Architecture-Malan] https://www.ruthmalan.com/Journal/JournalCurrent.htm, Ruth Malan

- [HR-Architects] https://www.slideshare.net/matthewskelton/accidental-architects-how-hr-designs-software-systems-team-topologies-nav-20200123, Matthew Skelton

- [Inverse-Conways-Maneuver] https://www.slideshare.net/Codemotion/microservices-and-the-inverse-conway-manoeuvre-james-lewis-codemotion-rome-2017, James Lewis

- [Microservices-North] https://speakerdeck.com/tastapod/microservices-software-that-fits-in-your-head, Daniel Terhorst-North

- [Team-Topologies] https://teamtopologies.com/, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais

- [Team-Topologies-Key-Concepts] https://teamtopologies.com/key-concepts, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais

- [Cognitive-Load-Assessment] https://github.com/TeamTopologies/Team-Cognitive-Load-Assessment, Team Topologies

- [Domain-Driven-Design] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain-driven_design, Domain-Driven Design book, Erick Evans

- [PM-Research-Alpha] How Product Management is Evolving: Findings from the 2020 PM Insights Report, Alpha

- [Dual-Track-Agile] https://medium.com/@daviddenham07/dual-track-agile-the-secret-sauce-to-outcome-based-development-601f6003ea73

- [Spotify-Engineering-Culture] https://labs.spotify.com/2014/03/27/spotify-engineering-culture-part-1/, Henrik Kniberg

- [First-Principles] https://jamesclear.com/first-principles, James Clear

- [Target-Operating-Model] https://www.thekua.com/atwork/2019/06/introducing-the-target-operating-model/, Patrick Kua

Changelog

- 22/09/2020: “Beta/RFC”, first public version of the article published (open “Request For Comments” - RFC)

ℹ️ I offer consulting services and products on this topic

If you are looking for help on these topics feel free to contacting me, and/or check my consulting and products pages for more details on how I may be of help.