Engineering Strategy, Will Larson

[Article]

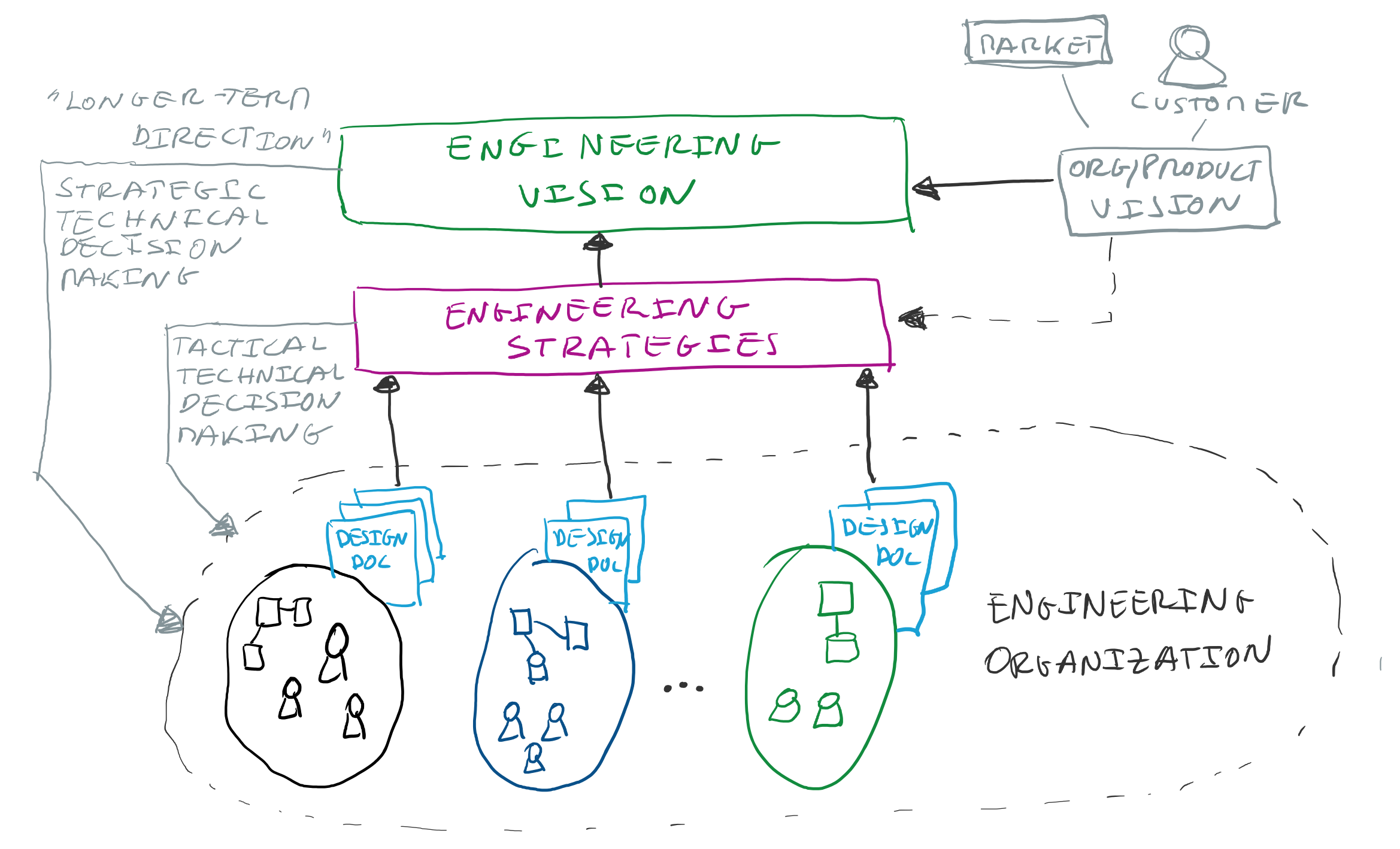

My Insights: this article by Will Larson is a rather interesting and refreshing way to approach setting and continuously operate Engineering/Tech Strategies and Vision. Classically Tech Strategy and Vision tend to focus on “ambitious points” and rather long windows of time, plus mostly driven by the company and product vision and strategy (i.e.: top-down). Will takes a completely different path in this article by proposing a bottom-up approach that continuously focuses on spotting the relevant engineering challenges, which arise on multiple “design documents”. The common challenges and approaches to solve them define the Engineering Strategies (in a nutshell: a pattern solution/guidelines to a problem context, which enables anyone facing the same issue to speed up their technical decision making). As more and more of these Strategies are identified, we can start defining longer-term strategies (or Engineering Vision), which consolidate multiple strategies into more stable longer-term vision on important topics (2-3 years time). This approach surfaces the significant strategies for the organization, which enables teams to speed up their decision making when faced with similar problems. By being driven by the “problems faced by the teams” we get a winning factor that is rather challenging on other Tech Vision and Strategy approaches: “self-evangelization” of the strategies. Teams basically see their input consolidated into an enriched and improved version, which means they are more likely to buy-in into those strategies instead of looking at alternatives. One element, also mentioned in the article, is that for longer-term strategies it is crucial to not just look at the Design Documents, but bring in extra context to enrich the decision making guidelines. This is rather important for “big shifts”, normally influenced by changes in product vision, or business strategy. It is crucial to consolidate those and bring them in so that new Design Documents take those in consideration (and automatically they get updated on the Engineering Strategies, which becomes a life-cycle of learning and improving design decisions).

Analysis & Summary

The insights and notes of this record are inspired and driven by an article from Will Larson that describes a “recipe” for shaping and defining “durable and grounded Engineering Strategies and Vision”. This approach is rather interesting as it takes an “iterative bottom-up learning approach” where we observe the common big engineering challenges (from Design Documents on teams) and from there synthesize the (current) relevant Engineering Strategies. Then, to provide extra longer-term direction, Will proposes an extra layer focusing on Vision, which extrapolates how the different Strategies (and their relations) pan out on a 2-3 years time window. This paragraph pretty much summarizes the proposed approach:

To write an engineering strategy, write five design documents, and pull the similarities out. That’s your engineering strategy. To write an engineering vision, write five engineering strategies, and forecast their implications two years into the future. That’s your engineering vision.

Strategies and vision are excellent mechanisms for pro-active alignment: they provide clarity for decision making on a particular context, which enables teams to move quickly and with confidence. This also avoids teams to “redo” a lot of investigation (i.e.: waste) and take very different decisions for no strong reason.

In the following I elaborate on the different phases Will mentions to setup and operate an Engineering Strategy. The sketch below presents my summary of the discussed approach (with some small extensions of mine, I call it “Engineering Strategy Life-cycle” as this really is about a life-cycle of activities).

<br

Phase 1: Write (at least) five Design Documents

- Why:

- In order to start identifying the relevant Engineering Strategies (and from there the Engineering Vision elements), we need to “understand” the relevant (and non-trivial) engineering problems in your organization and product(s).

- What:

- Design Documents (in some companies called Tech Specs, in others Request for Comments (RFC) documents). These are documents written by a team detailing the problem at hand and very concrete details on how to approach it.

- This document can be reviewed by people from outside the team. Such an approach can be a great mechanism to gather extra feedback; and also is a great way to share/align knowledge in the organization.

- Typical template: problem description; then ideas of possible approaches to solve the problem (does not need to be complete, but should be good enough for proper/productive review).

- The elements on the design doc must be sharp and very concrete (not just ideas).

- This is something that high-level/long-term strategies don’t have.

- Design Documents (in some companies called Tech Specs, in others Request for Comments (RFC) documents). These are documents written by a team detailing the problem at hand and very concrete details on how to approach it.

- How:

- Write Design Document (prefer good over perfect, which takes too much time to complete) and gather feedback.

- Gather input from different people (e.g.: in the form of RFC), but have one person writing the document alone. This makes sure the message is clear and sharp (instead of multiple styles mixed in the same document).

- Create at least 5 of these documents to be able to go to phase 2.

- Write Design Document (prefer good over perfect, which takes too much time to complete) and gather feedback.

Notes: Will mentions five documents, in my view this is just an indication and once we have identified the most relevant strategies this will be a continuous effort, as a function of learnings. Will provides a great pattern to approach this: “if you see the same discussion three of four-times, it’s time to write another strategy”. I really think this is a great way to continuously “calibrate” strategies and surface learnings into actionable knowledge that the whole organization can use.

Step 2: Synthesize the five design docs into a Strategy

- Why:

- To highlight the relevant and controversial decisions that happen in multiple designs. These particularly hard to agree points are the ones that require a common shared agreement (e.g.: what database technology to use for each use case in the organization).

- If we consolidate the “best approach for us” for certain (classes of) problems, we provide guidance and alignment for the whole organization, which enables teams facing the same problem to “just use” those Strategies (and focus on solving new problems), instead of spending(duplicate) time on solving the same problem.

- What:

- Strategies: defining the context of the problem and providing a good overview of the tradeoffs made to accomplish a guidance/recommendation.

- How:

- Take five recent design docs and identify the points that generate the most “controversy” and “discussions”.

- Write the specifics and concrete problems at hand. (Great advice from Will: “Write until you start generalize, and then stop writing”)

- “Be opinionated”, but also provide clear reasons to back the decision made (this will most likely be linked to the points identified in the Design Docs - especially the different views that different docs may have).

Notes: A Strategy becomes like a “pattern” (I call these more “Tactical Technical Decision Making” strategies). They provide direction for addressing a given problem that fits a context. This is really interesting and enables speeding decision making by teams when they face this “problem pattern”, e.g.: when building a new application/service handling a certain type of data or requiring certain properties, they can refer to the strategy for database selection and in matter of minutes have an informed decision on which database to use (well supported by the organization, tested by other teams, etc.). I think the approach that Will presents towards scoping a Strategy is in some cases close to the TechRadar methodology [Tech Radar], i.e.: it provides guidelines on technologies, methods, frameworks and platforms recommended (and not-recommended) within an organization. TechRadar may not cover all possible engineering strategies required by an organization, but may be a great way to complement and visualize Technical Strategies.

Step 3: Extrapolate five (recent) strategies into a vision

- Why:

- As we gather more and more strategies to address particular patterns of problems, it will become challenging to reason about the directions that these strategies define - they may even be contradictory or their scope too narrow.

- By reasoning on multiple relevant strategies and defining “higher-level strategy” (or “Vision”), which considers a window of 2-3 years time, we provide more clarity and direction to the technical decision making process.

- What:

- Vision document: defines strategies that are relevant in a longer time window, and with that providing clearer guidance for decision making (especially on non-trivial topics, ones that may require rather big investment or effort - “provide a robust belief in the future”).

- How:

- Start from the most relevant and up-to-date Strategies and look for the contradictions and challenges you see.

- Write vision elements considering a window of 2-3 years, so it can provide some “stability” for significant technical decisions to be made.

- For well established companies, this can be an even longer window of time.

- Consider business, product and user context:

- This input should be made explicit and influence the Vision so that teams can use those and make better technical decisions without having to (again) do all of that analysis themselves.

- Keep it to one or two pages long, should be a readable/usable document and one that does not change very regularly (stability is an important trait for Vision).

- Once you have a reasonable version, share it widely across the engineering organization for validation and consolidation.

Notes: vision elements are an harmonization and direction setting mechanism. They consolidate multiple forces into clear and actionable directions for teams in a longer-time window (I call these “Strategic Technical Decision Making” Strategies or Vision). Given they are created based on Strategies (which are based on Design Documents), they tend to be “recognized” by the engineering organization, and as such should not raise a lot of questions. If questions are raised, this is a smell that something must still be sharpened up. As Will mentions: “a great vision is usually so obvious that it bores more than it excites. Don’t measure vision by the initial excitement it creates. Instead measure it by reading a design document from two years ago and then one from last week; if there’s marked improvement, then your vision is good.”

Will has many interesting insights throughout this article, but at the end it sort of boils down to the fact that: “good engineering strategy is boring, and that it’s easier to write an effective strategy than a bad one”. There is a lot to unpack in this sentence, but in a nutshell the main point is: if we focus on addressing the “concrete problems” the different teams are facing and drive our strategies out of that we will be most likely addressing the important strategies (which seems boring, no “brilliant new ideas”, simply address the problems you are facing). By sticking with that we are driving our strategies based on “bottom-up organization learning”, which makes them grounded and connected.

References

- [Tech Radar] https://www.thoughtworks.com/radar

InsighTweet

💡 #TLA_insights: Engineering Strategy and Vision should be a "life-cycle" based on the concrete problems (& designs from teams), providing extended enriched insight to guide and speed-up future technical decision making.

— Eduardo da Silva (@emgsilva) December 15, 2020

References: @Lethain

+details ⤵️https://t.co/ATEvQM1Y2h