Less is More with Minimalist Architecture, Ruth Malan and Dana Bredemeyer

My Insights: This short article Ruth Malan and Dana Bredemeyer is packed with insights on how to approach and balance architecture activities in tech-enabled organizations. I resonate a lot with the proposed ideas, especially the striving for a minimalistic architecture approach: “doing just enough” (i.e.: no more, no less). What does that mean? Architects (and/or whoever drives architecture decisions) should focus on addressing the system priorities so that the teams working on those particular elements of the system can maximize their effectiveness for the overall system (instead of a “local optimization”). This approach also strives for leaving the maximum amount of room on decision making for teams working on the “more narrowly scoped” elements of the system, instead of overdoing those decisions from the higher-level system perspective.

Analysis & Summary

The insights and notes of this record are inspired and driven by an article from two current thought leaders on (Sociotechnical & Software) Architecture developments: Ruth Malan and Dana Bredemeyer. This short article shares several insights they have on how to approach architecture. The article is from 2002, but it is as up-to-date and relevant as it can get. They propose a “minimalistic approach” to architecture, namely: “sort out your highest-priority architecture requirements, and then do the least you possibly can do to achieve them”.

The article has the following structure: what are Architecture Decisions; then go into the challenges on Limiting Architecture Control and Insisting on Architecture Control; and finally discuss how to Empower with Scope. In the following I will go over these elements, highlight several quotes and elaborate on them, adding my own insights and reflections.

Architecture Decisions

“Architectural decisions are those that must be made from an overall system perspective.”

This is a great quote, which in my view emphasizes why having architects (or people that take explicit care of architecture decisions) are key to enable organizations to operate effectively. The reason comes from the fact this “overall system perspective” type of work we do to support building out software products (in smaller parts / teams) tends to have unclear ownership. It defines the “bigger system” where normally teams work falls into (these are key ideas of Systems Thinking). If we don’t have anyone able (or ways to capture) that holistic understanding, we will not be able to have the necessary context when working on the different parts of the system (i.e.: on the parts that are owned and built by different teams). This is why it is key to have proper ownership of a system’s architecture.

“Essential decisions identify the system’s key structural elements, the externally visible properties of those elements and their relations.”

These system-level essential architecture decisions tend to focus on key structural elements (e.g.: how do different teams and parts of the system are evolving) and their external visible properties and relations.

“If you can defer the decisions to a more narrowly scoped part of the system, it is not significant to the system level architecture.” (“more narrowly scoped” wording is a 2021 update suggested by Ruth Malan to previously “lower level” term previously used.)

“The only justifiable reason for restricting intellectual freedom of designers and implementers is demonstrable contribution to strategic system properties that the organization could not otherwise achieve.”

However it is key to not overdo Architecture decisions. As the two previous quotes emphasize, whenever we can defer a decision to a more narrowly scoped part of the system, we should do it. Teams have ownership of decision making on this. It becomes part of the internal application architecture, which must deliver the expected interface behavior or “visible properties” and relation with other related parts of the system.

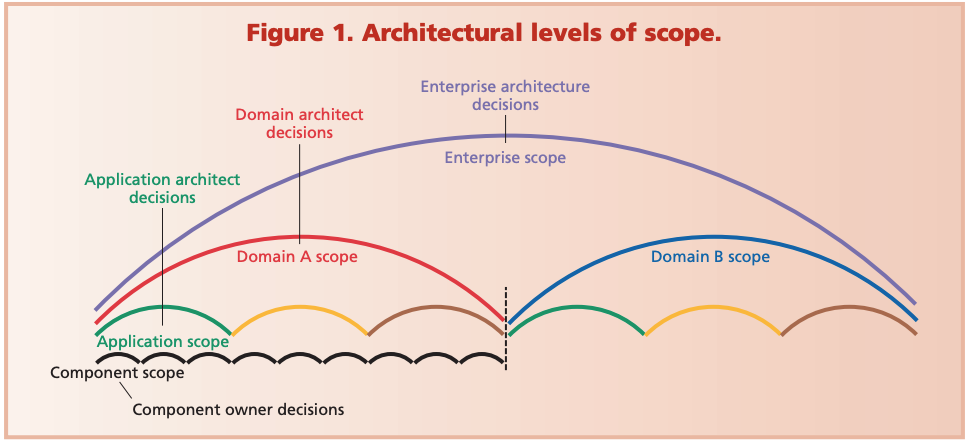

Figure 1 provides a nice overview on typical levels of scope within an organization. I think nowadays we may use slightly different terminology (remember the article is from 2002), however the core idea is pretty much to the point: there are scopes of decision making, which enable clear boundaries of decision making. This fosters autonomy while providing a connecting structure from more narrowly scoped parts of the system to the externally visible properties of the system we want to build in the organization.

Limiting Architecture Control

“Lack of visibility into other parts of the system, schedule crunch, and communication overload—many factors cause developers to make decisions optimized for a local scope and often suboptimal for the overall system.”

Nowadays there is some reluctance on having Architects doing architecture outside the scope of a team. There may be some good reasons for this - like “not doing good architecture” (too much, and centralized, up-front-architecture) or the so-called “ivory tower” architect. Those are definitely things we want to avoid while doing architecture! However, the solution should not be “not doing architecture”, since then we fall into the “local optimization” trap.

This is why it is key to have systems-level architecture, which focuses on understanding and decision making and enables the more narrowly scoped parts of the system to have more context and better decision making. That will enable us to achieve our goal: “improve the overall system” properties and not just have local-optimizations. I often use my restaurant system metaphor to emphasize this: “you want to serve the best dish the chef can cook with the best wine we have in the restaurant without understanding if they are the best combination… they are (most of the times) not the best combination”.

“So, in addition to every other tough job you have as an architect, you must figure out the right balance of architecture and anarchy for your organization.”

“It is key to keep in mind that Architecture changes the way people must work, so don’t try to do too much too quickly!”

Being an architect (or anyone handling architecture decisions) can be tricky at times. Nevertheless, it is key finding the balance of decision making. It is also extremely important to be aware of how everyone (people) are being (or will be) affected by those architecture decisions. Sometimes (what looks like) “anarchy” is fine in certain organizations, especially organizations with stronger culture of enablement. However, in many other organizations that is just not always possible. Having that awareness is also key for approaching the evolution of the (sociotechnical) architecture of the system(s).

Insisting on Architecture Control

“If you take the other extreme: The Architect as a Governance Organization that avoids setting clear direction and decisions…”

This is the other extreme side of architecture control, which may overdo and end-up micromanaging the governance of all decisions at all scopes and system levels. This is what I mentioned earlier as the modes that created a “bad reputation” for architecture. Such an approach is definitely not desired as it limits the flow of decision making and overall effectiveness of the different parts of the systems.

“Keep your architecture decision set to the minimum needed to achieve the most strategic architectural goals. Then work with all levels of management to ensure that these decisions stick.”

To avoid the trap of “too much control”, we must strive for “minimum decision making” at each scope/system level to enable achieving the “end goals” we have for the system. I really like how Ruth and Dana state that “all levels of management” should focus on ensuring those “minimal decisions” stick and as such enable people working within those systems to take the reminder set of decisions (while relying on those higher level decisions made). In a nutshell, this is what Netflix calls Highly aligned and loosely coupled on their culture document. Their goal is to “spend time debating strategy together, and then trust each other to execute on tactics” to achieve those aligned goals.

Empower with Scope

“You might already be fighting the notion that architecture disempowers. To some extent, it is a hard truth that architecture does place limits and take away some autonomy… But the alternative is chaotic development that, frankly, is even more disempowering.”

The balancing act of doing “good architecture” is difficult, but when we strike the balance it enables achieving the “system properties” we are striving for. It does that by providing “enabling direction”, or “limits”, for the designers and implementers of the different elements of the system. I want again to raise the fact that the level of “constraints” imposed and “who does architecture” is something that will vary from organization to organization (as a function of their culture and maturity of their practices). However, I couldn’t agree more with the statement above: the system is made of parts and is the result of their interactions, and having a “chaotic development” approach where parts are evolving in complete isolation is “disempowering” (as the properties we want to see on the system will most likely not happen).

“One of the benefits of a good architecture is that structural elements with well-designed interfaces become the focus for design and implementation. This lets work progress on the structural units with greater autonomy—and small teams with strong ownership are the font of innovation and productivity.”

In my view this is the key element to strive for in good architecture: enabling teams with the context and elements that provide them with alignment with the overall desired system properties. With that “context” teams can take full autonomy and “creativity” to best architect the internal elements of those structural units of the system. It is important to note that this does not mean that teams may not participate in system-level discussions, quite the contrary, that is totally possible. The element key is that those system-level discussions must take place - independently of whom is leading/driving them. This is a point that many organizations still misinterpret, namely: that by having “architects” or discussions at systems-level scope jeopardizes teams autonomy, when it is exactly the other way around. This systems-level alignment enables teams to best own and evolve the system elements that they are responsible for!

InsighTweet

💡 #TLA_insights: striking the right architecture decisions balance, striving for a minimalistic approach, is key to enable "autonomous teams" on their scope & maximize the overall system properties.

— Eduardo da Silva (@emgsilva) May 19, 2021

References: @ruthmalan @DanaBredemeyer

+details ⤵️https://t.co/DCdTViyK4s